As the author of six books and several short stories (eight

books if pre-published counts), I have indulged in a lot of research. I use the

word indulge on purpose, because most of the time, it’s fun.

Wikipedia states that research (look again? look

differently? – see how I get carried away?) is defined as "creative

work undertaken on a systematic basis in order to increase the stock of

knowledge, including knowledge of humans, culture and society, and the use of

this stock of knowledge to devise new applications.”

I love that whoever wrote this Wiki

page described research as creative. For an author, the inventive part comes

when we synthesize the knowledge into something completely unique, a new

character, a fantastical society, or an ingenious philosophy.

Why would a fiction author do research,

you ask? For me personally, there are a couple of reasons (at least) and I

believe most of my author colleagues would agree with them.

First, a novel must

have credibility.

Yes, even if you are writing about a

completely fictional town. For my Emily Taylor Mystery series, my imaginary

village of Burchill, situated in the middle of Ontario, couldn’t sport

palm trees. The setting, even in a fantasy novel, needs to have some

familiarity for the reader or we’ll get completely lost. In a mystery novel,

the setting must be pretty real. Burchill is based on Merrickville, Ontario, so

I visited, used maps, looked up the geography and topography.

In a mystery, the plot is extremely

important. The Emily Taylor Mysteries taught me, often the hard and

embarrassing way, that a plot idea often leads to a myriad of investigations.

My novels aren’t police procedurals, but they do have policing in them. I

learned from some of my endorsers (e.g. author Vicki Delany) that I had to be

more accurate.

In The Bridgeman, my main character was

the operator of the lift bridge. I knew nothing about that – enter, research!

Not to mention puppy mills (heartbreaking knowledge to have), policing of small

towns, and First Nation territories.

For Victim, I ended up having to learn

about forests, caves, rescue operations, vegetation and First Nation

philosophy.

With Legacy, I expanded into child

protection services, hypnosis, oxygen deprivation, post-partum depression,

fires, provincial courts and churches.

For Seventh Fire, wrongful convictions

took up most of my fact-finding time.

Sweet Karoline involved history,

pow-wows, policing in the US and Canada, and even more thoroughly, psychosis.

See how one little plot points feeds

the research machine? And the author simply must do it – otherwise, your

readers will pounce on you and refuse to buy the next one.

“The greatest part of a writer’s time

is spent in reading, in order to write: an [author] will turn over half a

library to write one book,” said Samuel Johnson, an English author in the

1700’s.

Do fiction authors have to be

completely accurate? Well, no. We are writing a story, after all, one that’s not true. However, we must find the

balance between reality and imagination to be believable.

Mark Twain famously said, “Never let

the truth get in the way of a good story.” This quote has often been translated

into “the facts” rather than the truth, but I suppose it means pretty much the

same thing. I somewhat adhere to this philosophy. I gather the information,

then sometimes bend or twist it to fit my purposes.

As Stephen King said, “You may be

entranced with what you’re learning about the flesh-eating bacteria, the sewer

system of New York, or the I.Q. potential of collie pups, but your readers are

probably going to care a lot more about your characters and your story.”

That’s often what I’m betting on when I

brush a bit too quickly across the truth or leave out some minutiae.

The second reason for doing research is

a big more esoteric. As Robert McKee, the creative writing instructor known for

“Story Seminar” has said: “Do research. Feed your talent. Research…wins the war

on cliché.”

Historical research for Sweet Karoline

led me to residential schools where Canadian First Nations children were confined.

Although these facts didn’t fit that book’s plot, I used the knowledge for The

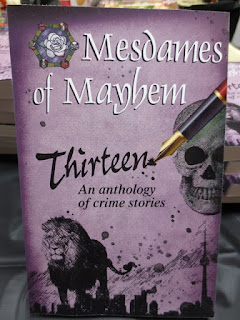

Three R’s, my story in the anthology Thirteen.

Currently, I continue

to read

everything I can about the schools. I live in Brantford, Ontario, where

the

Mohawk Institute sits – the model for all the other residences in our

country.

Ironically, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission has just begun to

make many of my fellow Canadians aware of this shameful past. Some day, I

believe a novel on this topic is destined to burst forth from my

fingertips.

I like that. Including some of the most

poignant, interesting or vital facts can make the story more vibrant, realistic

and distinctive.

“Research

is one thing: passion,” said poet Khalid Masood. Very poetic and, I think, true.

Next Time: A Creative Scrutiny

of Research Part Two Subsection A: The Author Asks How to Research?

To find all my books and short stories, visit my website: www.catherineastolfo.com

8 comments:

So true, Cath. Research makes a book come alive. Readers can relate to something they know to be true. Even when writing the Land's End fantasy series, I did massive research into Roman warfare, Viking armor, Satanic wedding rituals and wording. Yes, the books took place in an alternate ancient England, but I tried to stay as true as I could to the peoples and ages I brought into the story, to make it real for the readers.

Well, you hit the nail on the head, Cathy! Research is certainly fun, and a writer can get lost for days learning about something that will end up as a sentence or a paragraph in a novel. I can't count the hours I spent researching the Corpse Flower (Titan Arum) for my novel of the same name. I don't regret a minute of it. For my Cornwall & Redfern mystery-in-progress, I just learned how to activate a hand grenande. Good times ahead for my protagonist!

This reminds me of the first rule of science fiction - which I cannot find a source for despite my efforts which resulted in at least 19 rules and twenty lost minutes.

Only expect your audience to believe one impossible thing. Everything else should either be the logical result of that one thing, or based on fact.

I find this works equally well for crime fiction as science fiction. The impossible thing may be that an amateur detective keeps getting to solve police cases (with or without their approval) or that one small town can generate more murders than most major cities.

Let's try this again.

When I was writing Deadly Legacy, (which had the working title "Legacy" when I first met Cathy) I did a huge amount of research on police services and homicide investigation. I especially wanted to make sure that I was true the way Canadian police worked. (The media is inundated with information about US cops.)

Now my family can't watch a show without me pointing out when the fictional cops do something wrong or something that wouldn't happen Canada.

So very true, Cathy! Research is one of the fundamental tools all authors need to do. As an historical fiction author, I do an obscene amount of research for my books. I want to be as true to the time as I possibly can. What makes this difficult is that I have never been to Colonial America in 1723, or Colorado in 1887... therefore the research is necessary. I love to learn about the lives of the people who lived before me, and I an always learning new things. However, what really sucks is when I research for days only to use a minuscule amount within the book.

I did this in Blood Curse, where I delved into Merchant ships for hours...only to write one paragraph about it in the book. Ahhhh, the life of a writer. :)

Research is still an important factor even when writing fiction. To write fiction that is accepted by a reader, you must "suspend disbelief," no matter if you're writing fantasy or a thriller. Readers must BELIEVE your world, your characters and your plot. They need to believe them to be possible. And one of the best ways I've found to do this is to research elements of characters, setting and plot.

If your character is a recovering addict, research addictions and learn how this character might act. If she's a private investigator, interview one.

If your setting is in an actual town/city/country, research the area and point out key locations. Put your readers INTO that setting by painting a realistic picture--which is what research will give you.

If your plot deals with scientific discoveries like nanobots, research nanotechnology. If your plot deals with arson, learn about fires, how they start, their triggers, etc.

It's ironic that in school I hated doing research. But now that I'm an author, I absolutely LOVE it. I believe that research is the difference between a light, quick read that you quickly forget and a deep, informative and entertaining read that submerges you and won't let you go--even after you put the book down.

"It's ironic that in school I hated doing research. But now that I'm an author, I absolutely LOVE it."

True for me too, Cheryl. Mind you, when I was in university, I had to wade through card catalogues and microfiche to get to the information I needed. No Google to help me out and I still had to vette my sources before I could use the information.

Post a Comment